New Yorker article

From The New Yorker:

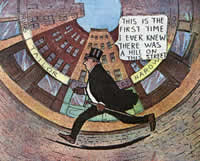

But the trailblazer of this mode, Harvey Pekar, is not a cartoonist at all, barely a writer, and well past adolescence, at least chronologically. Pekar, a lumpish Cleveland file clerk, came to public notice in several appearances on the David Letterman show, in the mid-nineteen-eighties, and was portrayed by Paul Giamatti in “American Splendor” (2003), a movie based on comics that Pekar wrote and others drew. A jazz and comics buff blessed with a connoisseur’s taste and remarkable powers of persuasion, Pekar met Crumb in Cleveland in the sixties and enlisted him to illustrate long, grumpy monologues that told the story of his shambling existence. (Desultory personal content in a bravura visual form quickly became fashionable among younger artists, most of it quite bad.) Pekar has since dragooned several other cartoonists to his exquisitely tedious ends. The latest is Dean Haspiel, who performs with virtuoso flair in “The Quitter” (2005, DC Comics/Vertigo), relaying Pekar’s confessions as a working-class dude who grew up with little in his favor except a knack for beating up other dudes. Pekar reviews the futilities of his life with humorless fixation and zero insight. He is the accidental minimalist of the graphic novel.

I have a mixed opinion on Harvey Pekar. Though, I alert any and all Harvey Pekar fans to the ancient Underground comic book collection "Apex Novelties Something or Other Collection", floated about by the "we don't publish anything, but we still kind of mail order stuff out" underground comic outfit Rip Off Press. Therein is a two page gag cartoon circa 1974 written by Harvey Pekar, illustrated by one of the now half-forgotten but competent underground cartoonists found in Zap. I wish I had more details, but I only half thought "This is kinda strange" when I saw it, reading it from the Portland State University library.

The best first-person graphic novel to date, “Persepolis” (2003), and the second-best, “Persepolis 2” (2004, both Pantheon), are by a woman, Marjane Satrapi. They suggest a number of rules for the form: have a compelling life, remember everything, tell it straight, and be very brave. “Persepolis” is about Satrapi’s childhood in Tehran during the Islamic Revolution of 1979 and the Iran-Iraq War. “Persepolis 2” follows her to school in Vienna, then back to Iran, and again to Europe, perhaps for good. Her parents are upper-middle-class Marxists, whose extensive family and social connections and political involvement exposed her to the full tumult of the times. Her uncanny way of incorporating exposition, with nary a stumble in her pell-mell narrative momentum, immerses us in the lore of Iranian history and culture. Drawn in an inky and crude visual style that is as direct as a slap, the books track her imaginings and her passions, which are wonderfully responsive, though usually inadequate to the realities of the situation. It’s a comic strategy that maintains buoyancy even in the face of the oppression, torture, and death of people dear to her, without for a moment treating the ordeals of others as secondary to her own. Satrapi’s unforced empathy contrasts with the self-pitying tendencies that are common to first-person comics written by men. Her stubborn ingenuousness may cloy (she has said, “Instead of putting all this money to create arms, I think countries should invest in scholarships for kids to study abroad”), but we don’t go to graphic novels for political philosophy.

I haven't read Persepolis yet, though I should. The Oregonian featured it in the strangest of manners, placing it alongside some "real" novels in terms of how characters have developed between novels. Anyway...

A certain theoretical frenzy about comics today is understandable, as it has been in other art forms in periods of their rapid development—think of the debates about painting that roiled Renaissance Italy. But such intellectual arousal rarely precedes creative glory. On the contrary, it commonly indicates that an artistic breakthrough, having been made and recognized, is over, and that a process of increasingly strained emulation and diminishing returns has set in. Nearly all art movements are launched by work that, when the dust clears, turns out to have been their definitive, peak contribution. “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” looms over the busy ramifications of Cubism as “The Waste Land” looms over the modern poetry that it inspired. Accordingly, there may never be another graphic novel as good as “Jimmy Corrigan,” even by Ware himself—whose current serial in the Times Magazine, though tangy, bespeaks a style on cruise control. But if the major discoveries of the graphic novel’s new world of the imagination have already been accomplished, its colonizing of the territory, like its threat to foot traffic in bookstore aisles, has only just begun.

OUCH. Graphics novels have reached their peak, eh? Ugh. I agree with the comment on Chris Ware. I honestly don't expect to see anything really great from him again. He is a one-trick pony... and the structure he's developed can't really seem to get him beyond that one emotional state of mind he has for Jimmy Corrigan. (I loathe Rusty Brown, and find it obnoxiously 'in-jokey'.) Daniel Clowes, on the other hand, has shown the ability to churn out one original and distinct graphic novel after another: Ghost World, David Boring, and Ice Haven. (Never mind that store clerk who once had a conversation with a customer calling Ghost World "pretentious" -- even though, frankly, Ghost World isn't).

Give a respectful but wide berth to Japanese manga, which occupy most of the shelf space allotted to graphic novels in bookstores, their bindings as uniform as lined-up vials of generic, obviously addictive pharmaceuticals. Dutifully paging, right to left, through a score or so of translated manga, I register the buzz of platter-eyed characters engaged in well-designed, pointless violence. I pause at frames in which, amid suddenly silent ruins, some liquid or another drips with a sound that is invariably rendered plp plp plp. It’s not that styles of sheer sensation are contemptible, but once you’ve said “Wow,” you are close to having exhausted the subject. It is even a point of honor with action comics—as with action movies and action anything, like roller coasters—to leave us with only a suffusive, endorphin glow. As for the dizzying byways of shojo, kinky romance manga for girls, I throw up my hands in Caucasian senior-male bewilderment.

I don't know what to make of manga. I "get" Osuma Tezuka, and have a great appreciation for his Phoenix line. But beyond that... I guess Video Girl is charming, but... I've seen literally nothing else that grabs me. Beyond that, there is a bit in a Harvey Pekar comic where Pekar visits a Japanese comic store, and the Japanese store owner hands him what is basically the only adult or mature comic book. Pekar asks "This is it?", the store owner gives a sad nod. And thus punctures the myth that the Japanese comic scene is exploding with great reading. Hrm. Ah well.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home